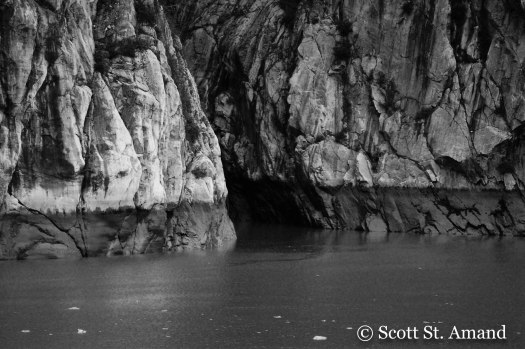

This photograph of Kemper was taken not too long ago at Big Talbot Island. He is in his element among the low-lying branches of the fallen live oak (Quercus Virginiana). Kemp is ever-cautious, and consequently has not broken any bones (so far). Even convincing him to climb the trunk, no more than four feet off the ground, took some coaxing. I am fine with his wariness of danger. It would have served me well as a child, who, by his age, had already broken both wrists and a couple of toes.

Despite his cautious nature, he is impulsive and fiery. His temper burns hot, though it is extinguished quickly with proper redirection. This has caused great consternation at school, where someone will call him a name, and he will explode momentarily. In that instant, he cannot control himself. I was not as impulsive as a child, though as an adult, I find myself irrationally upset at times, which quickly cools. I cannot help but think that he has seen me in such moments of weakness, where my sarcasm and passive aggression come through in full technicolor. I hate that he has witnessed this, and since his temper has blossomed at school, I have made every effort I can to dull my own temper — especially around him.

He is a sweet child, and wants nothing more than to make those around him smile or laugh. His intelligence is off the charts, but his emotional maturity lags behind significantly. Eventually this, too, will catch up (though I admit, I am waiting for my emotional maturity to catch up even at age 34). By every account, we are good parents, and he is a good kid. Nevertheless, since he returned from Christmas break, he has been sent to the principal’s office nearly every day by his young teacher, who appears incapable of managing his behavioral outbursts. He sees no point in doing the multitude of worksheets, on subjects that he has known since he was three or four, and he is overwhelmingly bored.

We have sat down with the principal, assistant principal, grade level chair, and his teacher, but the conflict between Kemper and his teacher persists. Anna, especially, is questioning our decision to place him at this particular school, which is, admittedly, rigid in its principles. Her years of training as a behavior specialist gives her great insight into how to manage children with his unique blend of intelligence and immaturity, which makes it all the more difficult to see him go unmanaged and unmotivated. This, too, shall pass, and we may move him before the school year is up. For now, we will provide him the positive reinforcement that he so thrives upon, and continue to embrace his unique personality. I will continue to bring him to Big Talbot, where he has begun to climb the trees with less and less coaxing, and I will pick him up when he inevitably falls.

Click here for a larger version.